Hamburger Bahnhof, Joseph Beuys, DAS ENDE DES 20. JAHRHUNDERTS, Ph: Thomas Bruns

There was a time when my body was just that, a body. Flesh, bone, a weight dragged through space. Then it happened. The fall, I don’t know whether to call it an accident, fate, or simply a beginning. I remember only the impact, the sharp cold, the silence thickening into matter. And someone, perhaps real, perhaps imagined—wrapped my broken skin in layers of warmth. Fat. Felt. Not to heal me. But to sculpt me.

From that moment, I understood: survival isn’t something you tell. Survival is something you shape. Survival itself is a sculptural act, a form that takes shape in the uncertain pulse of whoever remains. Every material I touch isn’t a choice. It’s a memory resurfacing in my hands. Fat is not a substance: it’s the first warmth I felt after death. Felt is not fabric: it’s the first boundary between my body and the world.

I can no longer tell where my skin ends and where the surface of things begins. I don’t create objects. I don’t stage stories. I am, each time, the object, the stage, the story itself. My body is no longer a refuge. It’s a square. A theoretical space where thought becomes flesh, and flesh becomes thought.

ICONS/ Sculpting Society: The Unfinished Revolution of Joseph Beuys

Joseph Beuys during the performance I Like America and America Likes Me, 1974

To speak of Joseph Beuys is to enter immediately into an ambiguous space where history and myth intertwine. Born in 1921 in Krefeld, Germany, Beuys did not simply live his biography, he transformed it into material. Central to this transformation is the story of his plane crash during World War II, an event that would become the founding narrative of his artistic identity. According to Beuys, after being shot down over Crimea in 1944, he was rescued by nomadic Tatars who saved his life by wrapping his injured body in animal fat and felt, materials that would later become emblematic of his work.

Whether the story is fact or fiction, and whether many scholars consider it a self-fashioned myth, is irrelevant. For Beuys, personal myth was never a lie. It was a sculptural material. A narrative not to recount history, but to construct meaning. The trauma of war was not simply a memory, it became the theoretical foundation of his practice. Fat and felt were not souvenirs of survival, but symbolic materials, charged with energy, warmth, and protection.

This event was not just biographical. It was conceptual. It signaled Beuys’ refusal to separate life from art. Survival itself became a methodology, and the body, the wounded, transformed body, the first medium. The artist did not create representations of experience. He treated experience itself as sculptural matter.

CONTINUE READING ↓

INTERVIEWS/ Fakewhale in Dialogue with the Jakob Collection: Rethinking Patronage and the Anti-Hero

A curious observer and unconventional collector, Lukas Jakob has turned his young age into a strength, building a collection that goes beyond simply accumulating works. His approach explores the fragilities, contradictions, and urgencies of our present moment. The Lukas Jakob Collection stands out for its focus on anti-heroic practices, complex digital processes, and exhibition formats that step outside the conventional white cube… (…)

Lu Yang, DOKU The Flow, 2024, HD Video, 50min 15 sec

Fakewhale:“I collect the present,” you’ve declared. But the present is never fixed. What are the signs, for you, that a work truly captures the spirit of its time and perhaps even pushes beyond it?

Lukas Jakob: My current interest lies in anti-heroic themes. A key impetus was Ulrich Bröckling’s essay Post-heroic Heroes, A Portrait of Our Time, in which he questions whether we still need heroes in a world structured by organization and technology, and how heroism is being redefined today. The classical hero has become obsolete, replaced by fractured figures who offer guidance not through greatness, but through humanity. I belong to a generation caught between resilience and exhaustion, between digital hyperconnectivity and social fragmentation. Our heroes are not triumphant, but ambivalent, overwhelmed, and complex. Portuguese photographer Jaime Welsh, for instance, uses editing software almost like a painter uses a brush. His staged images often show isolated figures in monumental, authoritarian-looking spaces. His meticulous process, from location scouting to post-production, creates psychologically charged scenes filled with tension and unease. Julian-Jakob Kneer tells the story of a masked anti-hero, drawing on visual codes from film and pop culture to explore fame, narcissism, longing, and self-destruction. When artists engage with pop culture, fashion, or politics, they respond directly to the urgency of the present. I’m also reminded of Rindon Johnson’s video I First You (11/11), which I acquired in the year it was created, 2018. It presents a floating, virtual landscape filled with voices reflecting on intimacy, loss, and political upheaval. The text, written on the day of Trump’s election, marks a turning point into a more violent reality. Personal moments, like the arrest of a loved one, mirror the political vulnerability of queer existence. Through these works I am also constantly learning new things about music, film, technology, history and sometimes deeply personal experiences.(…)

CONTINUE READING ↓

INTERVIEWS/ Curating as a Relational Practice: Fakewhale in Conversation with Giovanni Carmine

Giovanni Carmine, Portrait

In the landscape of contemporary art, the role of the curator has undergone a profound transformation in recent decades, becoming increasingly hybrid, complex, and influential. Giovanni Carmine is a key figure in this evolution: from his early beginnings in the Swiss independent scene to his directorship at the Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, and most recently as the curator of Unlimited at Art Basel, his trajectory reflects a constant dialogue between artistic research, curatorial precision, and an openness to emerging practices. In this interview, we retrace the key moments of his career, explore the changing dynamics of the contemporary art system, and ask how the role of the curator is being redefined today, between institutions, artists, and audiences.

CONTINUE READING ↓

INSIGHTS/ Gianni Caravaggio & Johannes Wald, “unforeseen” at Galerie Stadt, Sindelfingen

Exhibition view: "unforeseen", Gianni Caravaggio & Johannes Wald, curated by Hannah Eckstein, Galerie Stadt Sindelfingen, Sindelfingen.

The first thing we noticed upon entering was a hand. Or rather: a metal outline of its profile, suspended in the corner of the main room. Not an evocative shape, but a precise sign. It’s an appropriate starting point for reading unforeseen, the exhibition that brings together Gianni Caravaggio and Johannes Wald in a deliberately partial dialogue. Curated by Hannah Eckstein, the show doesn’t attempt a direct confrontation between the two sculptors’ respective approaches, nor does it search for synthesis. Instead, it builds a space of coexistence. Two distinct approaches to sculpture, one cosmological, the other self-reflective, are placed side by side without forced convergence. The distance between them becomes the real content of the exhibition.

The exhibition layout at Galerie Stadt Sindelfingen reflects this premise. The rooms are calibrated, sober, almost functional. Caravaggio’s works occupy the main spaces in a radial arrangement that emphasizes the idea of a constellation: works that reference each other without sacrificing autonomy. Wald, in contrast, fragments his presence across isolated episodes—niches, passages, interstitial spaces. Visitors are compelled to constantly shift perspective: from Caravaggio’s dense, formalized works to Wald’s traces of process. There’s no narrative flow, only a sequence of presences. (…)

CONTINUE READING ↓

EXPLORE THE LATEST ARTICLES↓

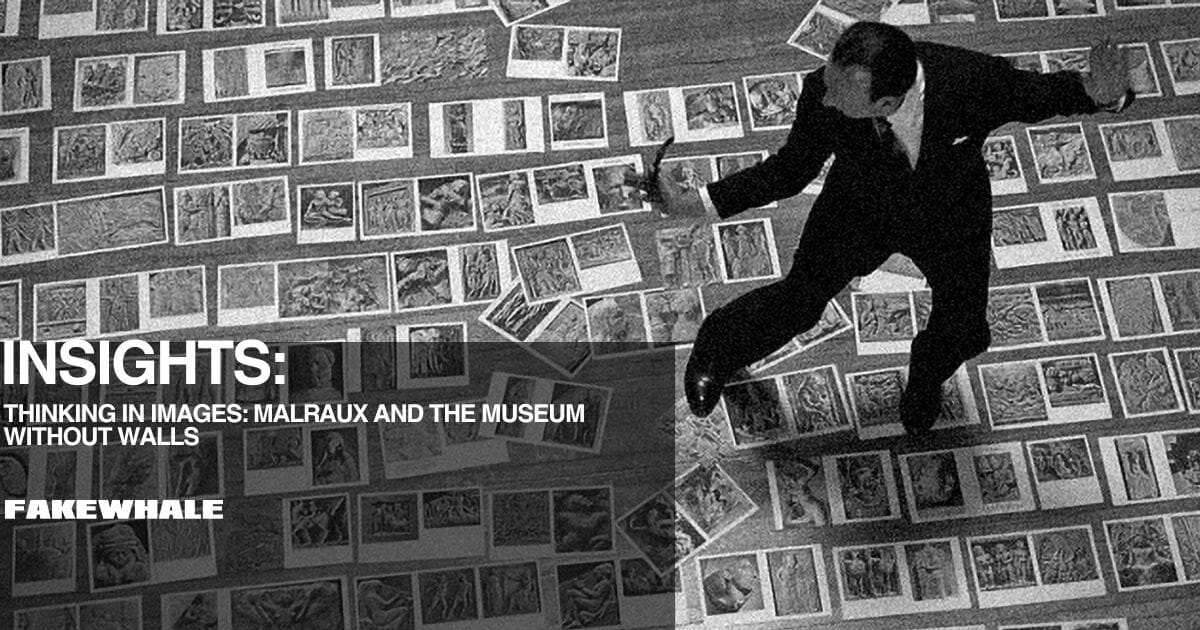

INSIGHTS/ Thinking in Images: André Malraux and the Museum Without Walls

The photograph of André Malraux, surrounded by a constellation of images laid across the floor, does not depict a moment of preparation or research, it enacts a gesture of creation. What we witness is not an editorial pause but an authorial act. Malraux’s posture, absorbed and upright, does not suggest passive observation but a form of embodied editing, a choreography of attention that elevates the arrangement of images to the status of expressive form. In this sense, the curatorial gesture ceases to be secondary to the work of art and becomes itself a work, a visual syntax through which meaning is not just transmitted, but actively produced.

This elevation of curating to the level of authorship emerges not through the institutional figure of the curator, but through a solitary and philosophical practice of montage. Malraux does not assemble an exhibition, he composes a visual argument. Each image on the floor is a fragment in a larger discursive architecture, a unit in a visual language through which historical time is collapsed and reordered. The act of juxtaposition operates as a syntax of affinities and tensions, turning the floor into a space of thought. The horizontal layout rejects any hierarchy between the images, it does not monumentalize, it activates.

To understand this gesture as artwork is to recognize its critical refusal of the traditional museum apparatus. There are no walls, no categories, no chronological progression. What Malraux constructs is a heterodox image-field, a mobile surface where sculpture from Khmer temples can appear next to a Renaissance figure, where a mask from the Congo can mirror the contours of a Greek kouros. This simultaneity resists historical containment. It proposes a way of seeing based on resonance rather than lineage, echo rather than origin.(…)

CONTINUE READING ↓

INTERVIEWS/ Blurring Boundaries: Yiming on Machines, Organisms, and the Future of Hybrid Art

Fakewhale: Your work often interrogates the tension between reality and simulation, life and mechanism. In Deceptive Behavior, you examine the illusion of consciousness and how we project sentience onto mechanical systems. How do you think our perception of “intelligence” is shifting today, especially in an era when machines seem to exhibit agency and autonomy?

Yiming Yang: Deceptive Behavior explores the tendency to interpret patterns of behavior as indicators of sentience or strategy. Intentionality is often projected onto systems that exhibit motion or structure, even in the absence of awareness. This reveals a broader perceptual ambiguity: the line between what is genuinely alive and what merely imitates life is becoming increasingly difficult to define. In this context, intelligence is not treated as a fixed attribute, but as a relational phenomenon that emerges through the interaction between body, object, and environment.

CONTINUE READING ↓

EXPLORE THE LATEST ARTICLES↓

That wraps this week’s issue of the Fakewhale Newsletter, be sure to check in for the next one for more insights into the Fakewhale ecosystem!