Fakewale Studio, Untitled,2024

At the moment when art became a book, a print, an ephemeral object or a postal letter, something in its very status shifted profoundly. The artistic gesture moved from gallery walls to the edges of the everyday, speaking a subtler, more radical, more intimate language. In that decade suspended between the late Sixties and the Seventies, conceptual art wasn’t seeking visibility but consequences: the object became a document, the exhibition turned into a message, repetition took on the weight of an urgency.

It was then that we began to keep everything. It wasn’t a deliberate act, nor a shared decision: we simply realized, one day, that we were already doing it. In the backrooms of our homes, in drawers that no longer closed and shelves crowded with papers, we accumulated clippings, tickets, fragments of ordinary days that were almost invisible. Every object seemed to turn into a hold, a silent clue to something we didn’t yet know how to articulate.

We called it, with a certain embarrassment, “our accidental archive.” An unstable assemblage of materials that none of us would have dared to call a collection. And yet it was there, and it kept growing. It was there that we found the first letter: a thin sheet, folded as if not to disturb. No sender, no date. “Every time you look at an object, you choose whether to let it be or to turn it into an event.”

We read those words one by one, then together, the way you read an omen. And before we could even discuss their meaning, another arrived. Then another. Each delivered in a different way: slipped between the pages of a book we thought we knew well; handed over with the morning bread; found in the pocket of a jacket we hadn’t worn in years. All written in the same small handwriting, all threaded with the idea that the world might be rewritten through small, silent shifts. (…)

Fakewhale in Dialogue with Michael Lowe

Marina Abramovic / Ulay , "Here is a sphere of change, Change, change, Through change consume change.", 1985, Offset printed post card, text on front: ,,Here is a sphere of change, / Change, change, / Through change consume change." - new address printed verso, hand written date 19-1-85, addressed to Peter v. Beveren, postmarked Amsterdam, Netherlands 12-85-20 [12-20-85]

In our conversation with Michael Lowe, a collector whose passion for 1960s and ’70s conceptual and minimalist art has shaped one of the most distinctive archives of its kind, we explored the intersections between memory, material, and meaning.

From his first encounter with Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise to his reflections on collaboration, analog collecting, and the evolving art landscape, Lowe invites us into a world where ideas take precedence over form and where collecting becomes an act of preservation, curiosity, and care. (…)

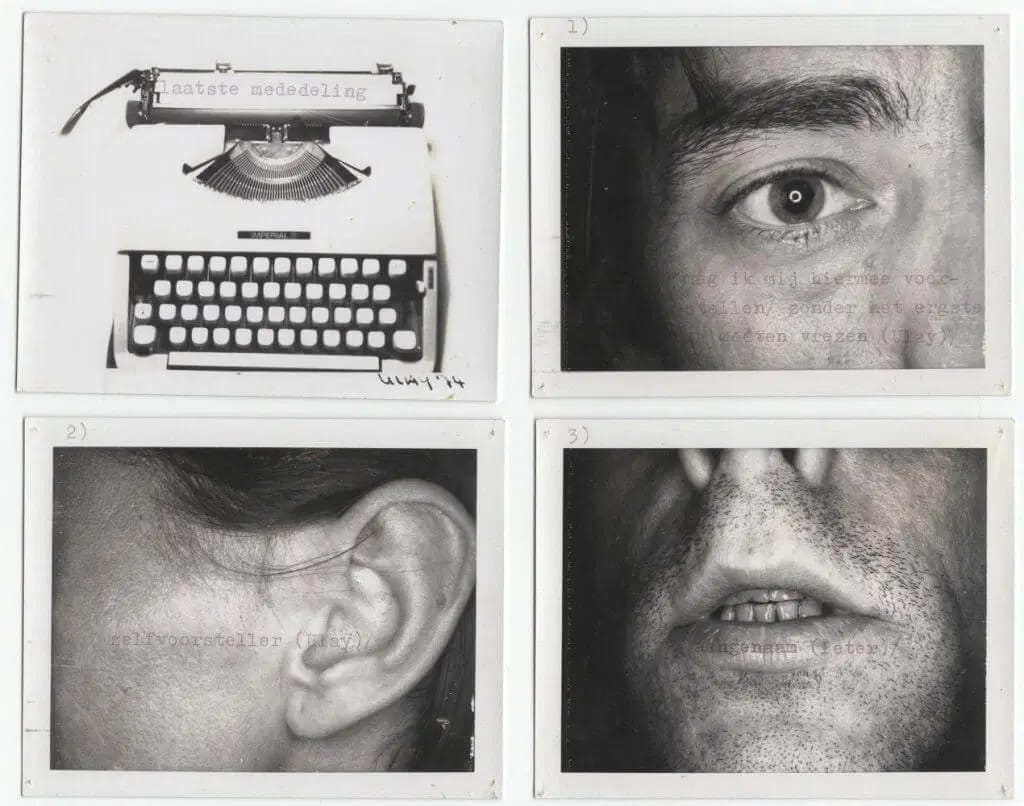

Ulay , " Laatste mededeling..." 1974 Nine b&w Polaroid photographs - eight with typed text over image, two signed and dated: (1) one photograph - correspondence salutation to Peter v. Beveren, typed text over the image a typewritersigned and dated (2) seven photographs one with typed text over the image a typewriter "laatste mededeling" signed and dated accompanied by six photographs numbered 1-6 detail images of Ulay's body with typewritten text (3) one photograph, no text, image of Ulay in a cemetery - coat hanging on a cross/gravestone

What criteria do you use when selecting works and artists that embody a radical conceptual mindset? And how would you describe what makes your collection distinct compared to others in the same field?

In selecting works, I have tried to select works which were, in their time, considered radical, based upon contemporary source material. By collecting primary documentation such as exhibition catalogues, magazines, books, and other documents, I began to view the works in their contemporary context.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the art world was not the art market. There were fewer collectors, fewer dealers, possibly two art fairs, and much less money.

I purchased European works for the most part, as prices were then much more reasonable for all art in Europe. Stanley Brouwn, Hans Peter Feldmann, André Cadere, Daniel Buren, Niele Toroni, Olivier Mosset, and Franz Erhard Walther represent radical positions taken and followed throughout their careers.

My collection possibly differs from most in this field in that I have collected in ancillary areas of the artists’ productions as well as their unique works: mail art, artists’ records, exhibition announcements, performance photographs, primary documentation, and films. The new art demanded experimentation in new mediums.(…)

CONTINUE READING ↓

DIALOGUES/ Fakewhale in Dialogue with :mentalKLINIK

:mentalKLINIK MICA, 2025 (PROFILE SERIES) SOFTCORE RADICAL, BACKROOM BABY, SELF-BANNED, AUTO-GLAM, POLITELY PARANOID, LOW-EFFORT ICON, HYPER EMPATH, SHAMELESS AI-generated sculpture, mannequin, artificial hair, silicone, clothes, shoes, chair, autonomous mobile robots (140.6 x 90 x 29.5 mm), sound, 91 x 93 x 114 cm Courtesy of PİLEVNELİ:mentalKLINIK’s practice unfolds like a prismatic, elusive entity, merging glamour with unease, surface gloss with hidden political strategies. A conceptual disco ball that refracts the codes of contemporary life, transforming installations, objects, and environments into fields of emotional tension, dark irony, and aesthetic seduction.

Fakewhale had the opportunity to speak with Yasemin Baydar and Birol Demir, the duo behind this hyperstimulated universe, to explore the origins of their visual language, the sociopolitical implications of their work, and the ongoing experimentation that fuels their research.

Fakewhale:Your work often presents a sleek, glamorous aesthetic, yet just beneath the surface, there’s a lingering sense of discomfort, ambiguity, or tension. How do you construct this apparent duality between attraction and repulsion, and what kind of perceptual shift are you hoping to trigger in the viewer?

We might say our work is repulsively attractive. From the beginning, we have thought beyond binary regimes—beauty and ugliness, good and bad, attraction and repulsion. These oppositions no longer explain the world we live in. Reality today is woven from contradictory forces that coexist and contaminate one another. We inhabit a sophisticated, opaque structure where pleasure and violence share the same code under soft power. Our oxymoronic approach is a tool to navigate that opacity.

Each work seduces to expose; every shimmer conceals a fault line as in our Painting Without Paint series Faker (2009–ongoing) the canvas becomes glass, functioning like a reflective screen. Painting migrates from surface to environment: brushstrokes dissolve into industrial layers, light acts as pigment, and transparency becomes deceit. Each piece is a truth test of vision—where reflection exposes what visibility conceals.

We live under a new kind of light—produced by invisible powers: algorithms, data flows, and surveillance technologies masked as transparency. The clarity of this world hides its own opacity. Glowing interfaces and seamless screens operate as cosmetic layers over deep excavation sites where our gestures, emotions, and desires are mined. We turn this smooth surface of hyper-capitalism into an instrument of friction. This is the affective texture of our time: frictionless interfaces, emotional speed and overstimulated calm. Our installations simulate this rhythm, not to condemn it but to make it suspicious.

Jack Halberstam describes :mentalKLINIK’s approach as counter-co-operators—we collaborate with the system precisely to expose its violence. Each exhibition becomes a seductive environment that performs complicity until it cracks. If awakening occurs, the exhibition turns into a torture house—an exquisite chamber where seduction starts to hurt.

EXPLORE THE LATEST ARTICLES ↓

REVIEWS/ Underneath the Paving Stone at Lunds konsthall, Lund

Exhibition view: Underneath the Paving Stone, Lygia Clark, Anders Hergum, Valérie Jouve, Yuko Mohri, Kasra Seyed Alikhani, Anne Tallentire, Carla Zaccagnini, curated by Karin Bähler Lavér, Lunds konsthall, Lund.

Underneath the Paving Stone by Lygia Clark, Anders Hergum, Valérie Jouve, Yuko Mohri, Kasra Seyed Alikhani, Anne Tallentire, and Carla Zaccagnini, curated by Karin Bähler Lavér, at Lunds konsthall, Lund, 20 September 2025 – 18 January 2026.

We enter through fissures. Not metaphorical ones, real cracks, imagined splits in stone and order. “Sous les pavés, la plage!” the May ’68 slogan reminds us: beneath the paving stones, the beach. The exhibition’s title, Underneath the Paving Stone, functions as both a battle cry and a lens, urging us to look beneath the visible, beneath the structure, beneath the illusion of stability. What lies beneath our feet isn’t just sand, it’s potential. And potential, we are reminded, is political.

From the moment we cross the threshold of Lunds konsthall, a subtle sense of destabilization settles in. The works breathe in quiet opposition. There is no noise, no spectacle. Sculptures, installations, and photographs coexist with restraint, like ruins waiting to be re-read. The air is still, but charged, as if the walls themselves were listening. Visitors move slowly. The rhythm is contemplative, as though each step might reveal something buried.

Exhibition view: Underneath the Paving Stone, Lygia Clark, Anders Hergum, Valérie Jouve, Yuko Mohri, Kasra Seyed Alikhani, Anne Tallentire, Carla Zaccagnini, curated by Karin Bähler Lavér, Lunds konsthall, Lund.

Karin Bähler Lavér’s curatorial hand is evident in the spatial dialogues she crafts between generations and geographies. Lygia Clark’s presence, ghostly, foundational, speaks across time with contemporary voices such as Anders Hergum and Kasra Seyed Alikhani. Their works don’t clash, they resonate. The architecture of the exhibition becomes a scaffold for rupture: materials are displaced, structures inverted, images untethered from their usual contexts.

Here, materials are never neutral. Anne Tallentire’s assemblages, made of found objects and residual traces, seem to archive impermanence itself. Valérie Jouve’s photography resists the documentary impulse, it fractures time and space instead. Yuko Mohri’s kinetic gestures transform invisible forces into audible whispers. There is humour too, often satirical, never mocking, hinting at pastiche and parody as modes of resistance. Pastiche here is a scalpel, not a mask. (…)

CONTINUE READING ↓

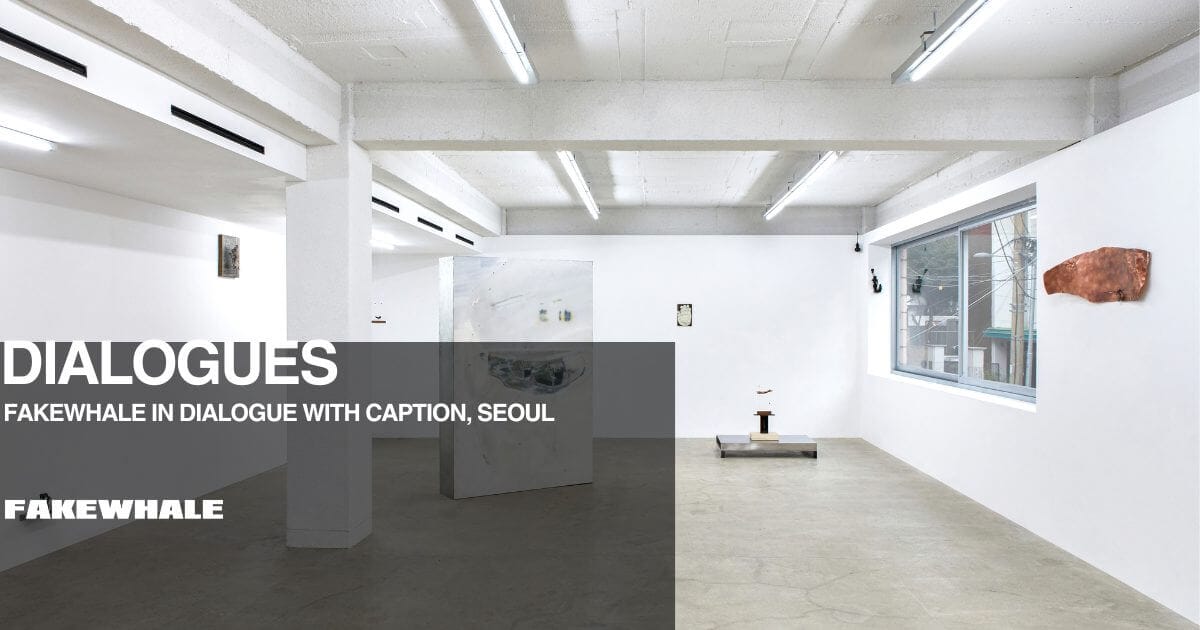

DIALOGUES/ Fakewhale in Dialogue with Caption, Seoul

Kay Yoon, Shu Da, Karu Miyoshi, Gilly Ghim, «間 Interstice», 2025, Caption Seoul, Photography by Bokyoung Han, 1

The contemporary Korean art scene is undergoing a profound transformation, and Caption Seoul has emerged as one of its most distinctive, fluid, and radically hybrid spaces. Born from a simple need for experimentation, it has evolved into a platform that bridges emerging artistic practices, design, and publishing, while continuously reflecting on the complex relationship between the art market and artistic language. At Fakewhale, we had the pleasure of exploring with them how to build a boundaryless curatorial vision in an era where access and cultural mediation are more crucial than ever.

Yeun Song, «On Off», KS-Tll, 2024, Caption Seoul, Photography by Yang Ian

Fakewhale: What motivated you to found Caption Seoul? After opening and over time, has your vision changed in any way?

Caption: We run both an art agency and a design studio, and have long been interested in practices centered around space. Caption Seoul began from a simple desire to create a place where we could freely experiment with things that intrigued us. As we were setting up our office, it naturally evolved into a space that could also accommodate exhibitions. In the beginning, our focus was not on commercial activity but on exhibitions and projects that genuinely sparked our curiosity.

After about a year of working in this way, we began asking ourselves, “Are we a gallery?” and eventually decided to define the space as one earlier this year. Since then, we have started participating more actively in the traditional art market, including art fairs.

This decision was shaped by the structural characteristics of the Korean art scene. While this may also be true elsewhere, in Korea the line between the commercial and non-commercial spheres tends to be particularly clear, and the term “gallery” is often equated with commerciality. However, as we continued operating, we began to question why one must choose between the two. Through many internal discussions, we have sought ways to present both directions simultaneously and are continuing to search for a balance between them.

Seongeun Lee, «NAUMACHIA», Falls 2024, Caption Seoul, Photography by Bokyoung Han, 4

The name “Caption” evokes the idea of a text accompanying or explaining an image. How is this concept reflected in the gallery’s programming and your curatorial approach?

We see “Caption” as a means of support for artworks, a channel that connects artists and audiences. Its role becomes even more important for those who may find art unfamiliar or distant. Of course, text can sometimes over-explain or confine an artwork, but we wanted to find a balance. We see our role as helping audiences understand the artist’s intent or the context of the work in a natural way, while also guiding them to sense and experience what may not be immediately clear. That is why we named the space “Caption.” For each exhibition, we prepare separate artist interviews or personally explain the exhibition to visitors. Unless an artist deliberately wishes to withhold information, we do our best to convey the meaning and sensibility of the work as clearly as possible. Perhaps because of this, visitors often mistake us for the artists themselves or for docents.

CONTINUE READING ↓

That wraps this week’s issue of the Fakewhale Newsletter, be sure to check in for the next one for more insights into the Fakewhale ecosystem!

1