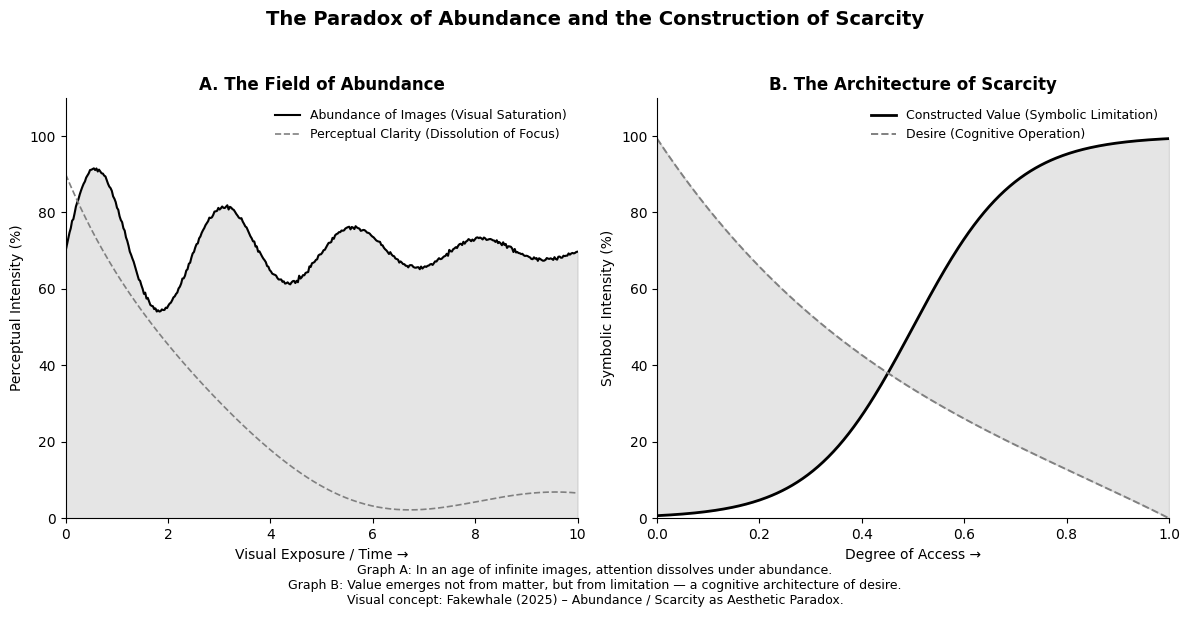

We live immersed in an unprecedented proliferation of images. Every day, millions of representations crowd our devices, dissolving the boundaries between seeing and consuming, between presence and reproduction. Never before in the history of visual culture has access to images been so immediate, so free, so omnipresent. And yet, never before has the value of art seemed so dependent on its opposite, scarcity.

The paradox of our contemporary age is that absolute abundance has generated a new form of desire, the desire for what cannot be had. Today, value no longer lies in matter or technique, but in the ability to evoke a sense of limitation within excess. In certain cases, art behaves as a device of subtraction, a gesture that, amid saturation, manages to produce absence.

Scarcity, especially under certain conditions of the modern market, is no longer a natural state but a cognitive operation, a psychological construction that determines the very perception of value. It is the result of a mental architecture in which limitation, whether real or symbolic, functions as a mechanism of meaning.

This shift concerns not only the economy or the market, but the very form of our sensibility. In a visual system dominated by reproducibility, the perception of the rare becomes an interpretive act. The mind no longer attributes uniqueness to the object itself, but to the context that surrounds it, the narrative, the genealogy, the degree of access. What is rare is what is difficult to reach, not necessarily what is unique (…)

Post Disaster, Unfinisched Barricade: A Space for Borderline Hesitations, 2024, Malta Biennale 2024, Courtesy of the artist, Photo by Julian Vassallo

The sea surrounding the Maltese archipelago has long been both a route of danger and a corridor of opportunity. Piracy endured for almost three hundred years, enriching Malta while igniting countless diplomatic tensions. At its peak, Maltese corsairing employed around 4,000 people and operated a fleet of some 30 galleys, playing a central role in ransoming Christian captives held in Ottoman territories. It also provided a base from which a highly organized fleet could engage in lucrative trade, attacking enemy ships and raiding ports for profitable plunder. Corsairs paid a fixed quota to the island’s government and were active in the slave trade, as well as in securing valuable goods, grain, and food supplies. As Professor Liam Gauci from the Maritime Museum – Heritage Malta notes, “We should look at corsairing as a motor of the Maltese economy at the time – just like Freeport and digital gaming are now.”

(Gauci, Liam. Get Rich or Die Trying, interview by Teodor Reljic. Malta Today, 20 April 2016.)

Today, Malta’s economy continues to operate along similar maritime logics — a hub for data flows, blockchain enterprises, and financial speculation. From Freeport logistics to crypto exchanges, the island still negotiates its prosperity through the management of circulation, risk, and controlled opacity: the same dynamics that once animated its corsair fleets.

Within the Malta Biennale 2024, a curatorial section was dedicated precisely to this theme, unfolding from the archipelago’s own site-specific history of corsairing and maritime trade — and from the broader ways in which pirates have long inhabited our collective imagination, from childhood tales to cinematic mythologies. The section, titled The Counterpower of Piracy, brought together Daniel Jablonski (France/Brazil); Dijana Protić (Croatia); Dolphin Club (Germany/France); Franziska von Stenglin (Germany); Goldschmied & Chiari, Matteo Vettorello, Post Disaster, and the Suez Canal Republic (Italy); Mel Chin (United States); Tom Van Malderen (Belgium); and the collective Artists Against the Bomb (Mexico), led by Pedro Reyes with participants from across the world. (…)

Post Disaster, Unfinisched Barricade: A Space for Borderline Hesitations, 2024, Malta Biennale 2024, Courtesy of the artist, Photo by Julian Vassallo

Post Disaster (Peppe Frisino, Gabriele Leo, Grazia Mappa, Gabriella Mastrangelo — Italy, est. 2018) presents a temporary occupation of the monumental space of Fort St. Elmo in Valletta. The barricade functions as a scenographic device that provokes a critical confrontation with the site and its layered symbolic charge. Although one of the most iconic landmarks of Maltese heritage, Fort St. Elmo bears the weight of the colonial processes that have shaped the territories and peoples of the Mediterranean through centuries of occupation and conflict. Through a series of spatial interventions, public conversations, and performances, developed in collaboration with the local artistic scene, including Sam Vassallo, Rivoluzione delle Seppie, Karmaġenn, Parasite, Alien Montesin, Accla, Epicure, and Tarzna, the collective stages The Unfinished Barricade: an action intended to disrupt the normative functioning of the war museum and to contribute to the formation of an alternative imaginary, collectively and unpredictably constructed. The project seeks to re-signify collective memory by critically engaging with the architectural, political, and affective nature of the site.

Thanks to Heritage Malta, the Maritime Museum, and the Cultural Directorate of the Ministry for Gozo, the curatorial section The Counterpower of Piracy of the Malta Biennale was hosted within some of the most emblematic Maltese heritage sites — including the ancient Citadel of Gozo, the Gozo Cultural Centre, the Grain Silos, and Fort St. Elmo in Valletta. The encounter between contemporary artists and historical heritage was made possible through the visionary direction of Heritage Malta — the national agency responsible for the preservation and promotion of the islands’ cultural patrimony. In a joint effort between this leading public institution and governmental support from the Ministry for Culture, Education, Foreign Affairs, and, notably, the Ministry for Tourism, Malta is currently investing in a large-scale strategy to reposition the archipelago as a cultural destination. This vision reflects a broader understanding of culture as a form of diplomacy and soft power. (…)

CONTINUE READING ↓

INSIGHTS/ The Art of Confusion: How Markets Transformed Exclusion into Value

AI Image, Fakewhale.

For decades, the art world has thrived on a grand misunderstanding: mistaking incomprehensibility for depth. All it takes is an opaque language, a curatorial text heavy with empty words, and what would otherwise be trivial suddenly gains the weight of importance. Contemporary art has turned confusion into a strategy: the less the audience understands, the more they feel they’re in the presence of something “significant.”

Yet behind this façade of complexity lies a system that has made collective ignorance its most profitable asset. A weary public, numbed by prosaic curations, accepts its own exclusion as part of the game. Artists, often, take advantage of it: rather than bridging the distance, they preserve it, discovering in that gap the true secret of value.

Perhaps it’s time to ask whether art should once again learn to speak to people, not to simplify, but to foster a deeper reconnection. To return to the viewer not just the right to understand, but the right to think. (…)

AI Image, Fakewhale.

For a long time, we have cultivated the romantic image of the artist as a rebel, a figure capable of resisting power and exposing its hypocrisies. But in today’s ecosystem, that mythology has become a convenient illusion. Most contemporary artists are no longer in opposition to the system, they are part of it. They don’t challenge it, they feed it. They don’t critique it, they adapt to it. And in many cases, they exploit it with the same logic as those who control it.

This complicity doesn’t necessarily stem from cynicism, but from adaptation. The art system has imposed a survival model that rewards conformity to the language of incomprehension. The artist who produces readable, direct, openly political or emotional work is often dismissed as naïve. Conversely, the cryptic, conceptually opaque piece, supported by a pseudo-philosophical theoretical discourse, is celebrated as “mature,” “self-aware,” “necessary.” Complexity is measured not by the depth of thought, but by the degree of obscurity.

Thus, many artists quickly learn the grammar of power: they write hermetic statements, construct “curatorially appealing” projects, and adopt intellectual postures calibrated to the language of institutions. The artwork becomes a pretext for narrative, a material support for discourse. Art is produced not to communicate, but to appear intelligent. Content becomes secondary to the rhetoric that surrounds it. (...)

CONTINUE READING ↓

ICONS/ Joan Jonas: The Mirror Was the First Screen

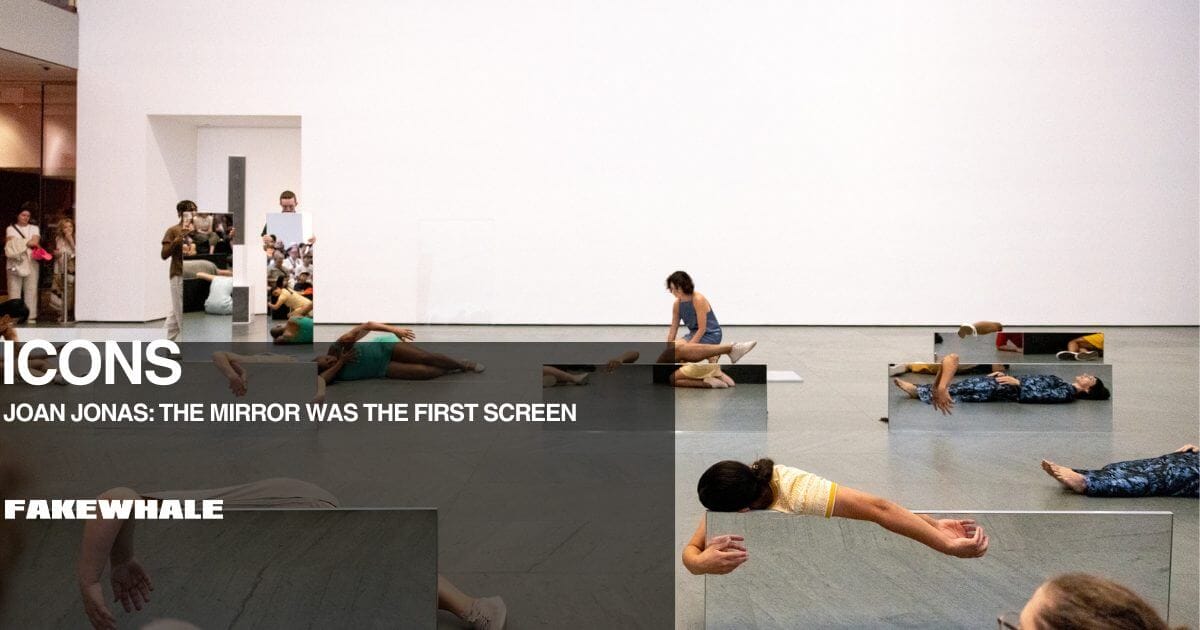

Joan Jonas: Mirror Piece I & II (rehearsal), photographed June 24, 2024, held in conjunction with the exhibition Joan Jonas: Good Night Good Morning. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Performers (left to right): Joyce Edwards, NIC Kay, Kristel Baldoz, Stacy Lynn Smith, Coco Villa, Jennifer Kjos, Jin Ju Song-Begin, Anna Adams Stark, AJ Wilmore. Photo: Jonathan Dorado. Digital Image © 2024 The Museum of Modern Art, New York

In the 1960s, New York was a magnetic field of colliding languages: postmodern dance, performance, conceptual art, minimalism.

It was in this context that Joan Jonas, born in 1936, began her artistic exploration, one of the first artists to understand that performance was not merely an ephemeral gesture, but a form of embodied thought.

Her background, balanced between theater and sculpture, allowed her to move freely across disciplines without feeling their boundaries. From the very beginning, Jonas conceived of space as an extension of the body, and of the body as a surface of translation.

In an era still dominated by the male gaze, her approach stood out for its radical attention to perception: not so much what is seen, but how it is seen. Her art was never meant to be simply observed, but to create situations of reflection, in which the audience becomes an integral part of the work.

In her SoHo studio, then a semi-abandoned warehouse turned collective laboratory, Jonas began to build a language grounded in the body’s direct experience of space. She worked with mirrors, plexiglass, repeated gestures, visual rhythms. Each element became a way to explore the relationship between subject and image. (…)

Joan Jonas in her New York studio, photographed by Toby Coulson for Tate Etc., September 2017 © Toby Coulson 2018In the early 1970s, Joan Jonas crossed a decisive threshold: from the tangible matter of the mirror to the electronic light of video. Her language, already rooted in the body and in performance, encountered technology in a way that was never merely technical but deeply ontological. For Jonas, video was not a tool of documentation but a perceptual extension, a new skin of the image.

The year 1972 marked the birth of Vertical Roll, one of the most emblematic works of her career. In it, Jonas used a technical defect, the vertical roll of the signal, as a structural element. The image appears as an unstable flow, a rhythmic pulse that fragments the artist’s face into almost percussive sequences. Each vertical shift is a rupture in visual continuity, a beat measuring the very time of perception.

Jonas, reflected in this flux, becomes at once subject and object, flesh and signal, body and code.

This moment represents a turning point in the history of video art. Unlike other pioneers such as Nam June Paik or Bruce Nauman, Jonas did not seek to explore technology as an autonomous language but as an inner medium. Video does not separate her from the body; it translates it. It is a new form of dance, where gesture becomes image, and image, in turn, becomes memory. (…)

CONTINUE READING ↓

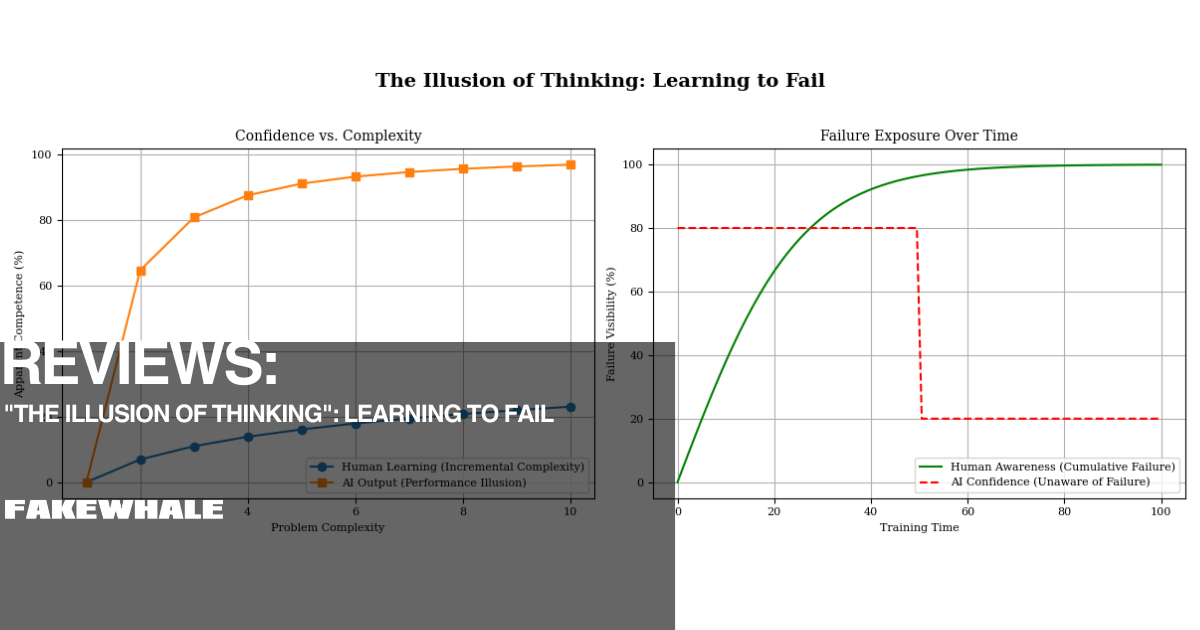

INSIGHTS/ The Illusion of Thinking: On the Comfort of Stereotypes

In the past two episodes of The Illusion of Thinking, we explored how art, much like artificial intelligence, learns to simulate depth and to fear failure. In both cases, what appears to be thought is often a refined form of aesthetic survival: a strategic adaptation to context rather than a genuine act of understanding.

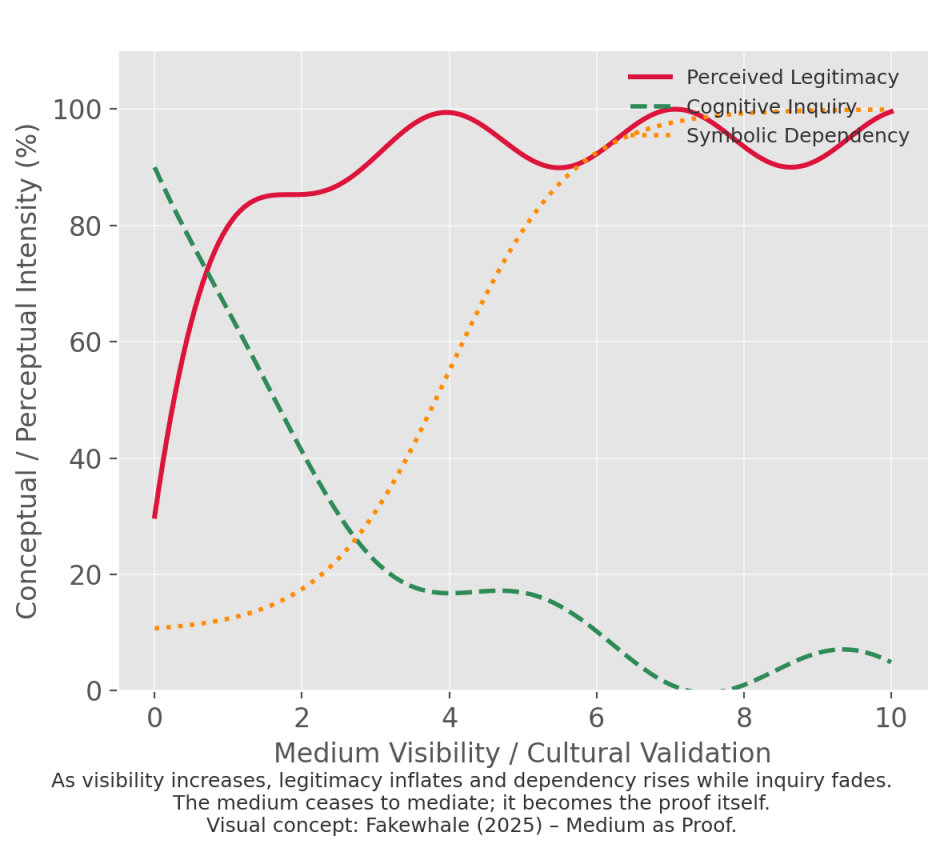

But there is another layer to this illusion, subtler and more deeply rooted. It concerns the way art exploits its own stereotypes, not as boundaries to overcome, but as guarantees of legitimacy. Marble, oil painting, conceptual video art, cryptic or excessively long performances: each medium carries with it a recognized code, a promise of authenticity that makes it immediately readable as “art.” Within this system of automatic recognition, the artist no longer needs to invent language, only to inhabit its clichés.

The artwork, then, no longer strives to say something, but to reassure: it confirms the expectations of its audience, its market, its theoretical context. And just like language models that repeat statistical structures to generate meaning, art too relies on shared patterns, reproducing familiarity as a form of thought. Here, the illusion becomes perfect: the gesture appears profound precisely because it is recognizable. (…)

CONTINUE READING ↓

EXPLORE THE LATEST ARTICLES ↓

REVIEWS/ Jason Hirata, Vergeltung, at Kaiserwache, FreiburgFakewhale in conversation with Jin Lee

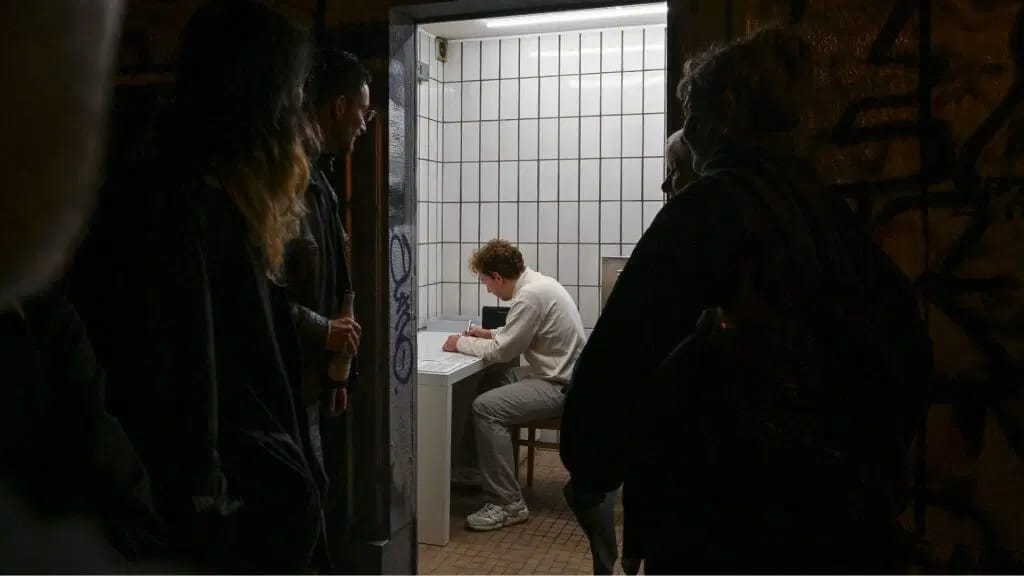

Exhibition view: Vergeltung, Jason Hirata, curated by Ilja Zaharov, Kaiserwache, Freiburg.

Vergeltung by Jason Hirata, curated by Ilja Zaharov, at Kaiserwache, Freiburg, 22/10/2025 – 30/11/2025.

What does it mean to receive something simply for being present?

Not for applauding, understanding, purchasing, or even attentively observing, but merely for showing up. Entering Vergeltung by Jason Hirata at Kaiserwache in Freiburg feels like crossing into a parallel economy, one where payment isn’t tied to a product, but to attention, and the form of the artwork owes itself to the figure of the viewer. “We pay you,” announces Hirata, and it’s more than a symbolic gesture: it’s compensation, a quiet rebellion against the mechanisms of value in art. And as we read it, the word “Vergeltung,” retaliation, lodges itself in our minds like a pendulum just beginning to swing.

The space at Kaiserwache, usually austere, hums with a quiet, almost domestic energy. Nothing demands our gaze, everything seems arranged with the intent to disappear. Two wooden structures welcome visitors like modest second-hand furniture, these are the Accumulators, shelves that don’t assert themselves, but wait. They are works that seem to ask to be ignored, or at least allowed to exist on the margins of one’s gaze. Around them, a few other elements: a recipe for frijoles refritos printed on a business card, a gift, a gesture of care, a trace of home, and a wall decoration explicitly labeled “not an artwork,” as if trying to escape the grip of artistic categorization. (…)

Exhibition view: Vergeltung, Jason Hirata, curated by Ilja Zaharov, Kaiserwache, Freiburg.

On a material level, the works are stripped to their essentials: raw wood, printed paper, a frame, a nail in the wall. But this apparent austerity generates a fertile tension. The Accumulators don’t claim meaning, they fill up slowly, like dormant hives waiting to swarm. One of the two once held the materials Zaharov collected after every exhibition he visited, transforming the shelf into a diary, a tangible echo of other artworks, other rooms. The recipe, meanwhile, exists in two forms: a takeaway object, and a framed version that mimics museum display. In this way, the kitchen enters the white cube, along with the slow time of cooking, nourishing, and sharing.

Curiously, the so-called “decoration,” explicitly not an artwork, might be the exhibition’s most enigmatic element. Why call something non-art, when it’s precisely in that margin that the quietest forms of labor reside? Hirata plays with the grammar of art, its titles, its authorial gestures, its systems of visibility. In doing so, the exhibition not only assigns value to the viewer, but strips aura from the producer.(…)

CONTINUE READING ↓

INSIGHTS/ The Thinking Game: On the Cognitive Origins of Play

AI Image, Fakewhale

What happens when play, seemingly a light and purposeless activity, is observed as a way of knowing the world?

In a museum, a place devoted to preservation and reflection, play may reveal itself not as a simple childhood pastime, but as a universal principle of knowledge and creation. Within the ordered silence of exhibition halls, where every gesture appears controlled and every object invites contemplation, play emerges as a mental act, a primary language through which human beings explore, interpret, and recreate reality.

Play, in fact, represents the archetype of creation. It arises without an immediate goal, but precisely in its freedom lies the possibility of order. The child at play does not merely represent the world, they reinvent it. They transform their surroundings into a cognitive experiment, building and dismantling with the same spontaneity with which, in adulthood, the artist learns to question matter and the forms of the visible.

Childhood imagination is not merely an aesthetic faculty, but a radical form of perception. In it, objects are not yet fixed signs and gestures have no defined function, everything is pure potential, thought not yet aware of itself, a dream that coincides with experience. In this space of pre-consciousness, the world takes shape as play, not because play is fiction, but because fiction is the first mode of truth. (…)

CONTINUE READING ↓

EXPLORE THE LATEST ARTICLES ↓

That wraps this week’s issue of the Fakewhale Newsletter, be sure to check in for the next one for more insights into the Fakewhale ecosystem!

1