Some time ago, there was an old man named Michael who lived near our house — the kind of man who could talk for hours without ever truly repeating himself. During one of his endless, meandering afternoons spent talking about art, he pulled out a crumpled piece of paper.

It was a circular diagram, hand-drawn in faded blue ink. “I made this in '60, with a couple of friends,” he said, “back when we still believed the world could be explained with a pencil and a bit of coffee.”

At its center was a single dot, and spiraling outward from it were words chasing one another: expressionism, conceptual, baroque, futurism, mannerism, arte povera, realism, neon, sacredness, glitch. A chaotic but oddly precise dance — as if each style, each impulse, were just a station along some eternal orbit. Art history not as a line, but as breath: cyclical, tidal, a kind of orbiting grammar that returns again and again, always with the subtlest shift in tone.

Michael, a failed linguist, in truth, spoke of art as a language that writes itself. Each movement a phoneme echoing across centuries, each current a temporal inflection of the same obscure urgency. The avant-gardes never truly erase what came before, they metabolize it. Returns are never just nostalgia; they are reincarnations. In art, every “new” is always a re-: reformulation, recombination, reappearance.

Perhaps there was never really a beginning, and there will never be an end.

Perhaps the true language of art is a Möbius loop, a circular pattern folding in on itself, like history, always returning in disguise.

ICONS/ Jason Dodge: From Minimal Gestures to Narrative Conditions, Where Objects Become Thresholds of Meaning Fakewhale in dialogue with Paula Ferrés

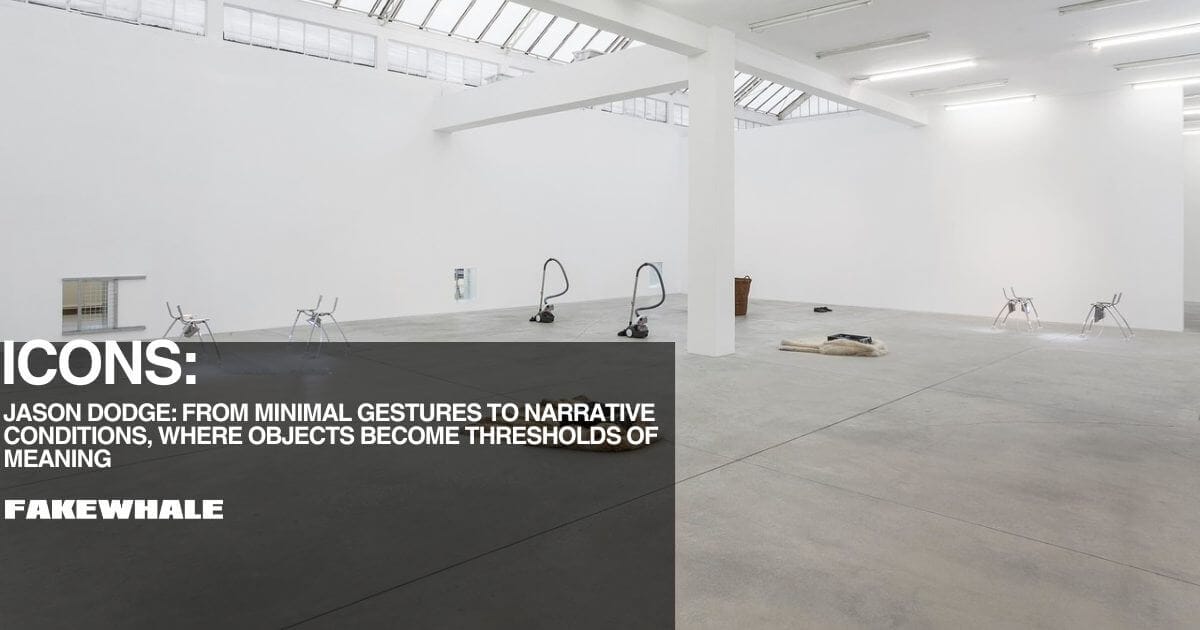

Jason Dodge, exhibition view. Franco Noero, Turin (two locations). Photos by Sebastiano Pellion di Persano. Images courtesy of the artist and Franco Noero, Turin, 2018.

We were leafing through the catalogue of an exhibition we had seen years ago at MACRO in Rome when Jason Dodge’s name began to resonate again from the pages, like a familiar call. Then we recalled that precise sensation: entering the space and not encountering a single work to contemplate, but rather an entire emotional context demanding to be read as a clue. There was no monumentality, no staging, and yet every detail seemed to contain the possibility of an infinite narrative, a kind of theatre of being.

Jason Dodge’s work occupies a threshold where the everyday object ceases to be inert matter and becomes a narrative vessel, a poetic fragment, a trace of an unseen story that nevertheless persists. Born in 1969 in Newtown, Pennsylvania, and active for years between Berlin and the United States, Dodge has built a practice that moves fluidly between sculpture, writing, and publishing, probing the subtle relations that bind things to language and sensory experience to narrative.

His work resists spectacle: it reduces, subtracts, and entrusts the viewer with the task of completing what the object only intimates without declaring. A woven fabric calibrated to equal a specific distance, a flute suspended to vibrate with a passing breath of air, a window left permanently open at the top of an industrial tower, these gestures reveal that the work does not coincide with form, but with the condition the form sets in motion. (…)

Looking at Jason Dodge’s early steps, one might be tempted to read them within a minimalist genealogy: ordinary objects, shifted only slightly, positioned in space with a sobriety that recalls Donald Judd more than a storyteller. Yet it soon becomes clear that the root of his practice lies elsewhere: in the constant friction between things and words.

Dodge does not simply isolate an object. He charges it with a title that does not describe but instead opens a story. A handwoven blanket is never called simply a “blanket”: through its title, it becomes the measure of a journey, of a distance traveled, of a life. In this displacement, the object ceases to be a “ready-made” and is transformed into a materialized poetic verse, a sensitive lexicon built of clues.

The literary influences are unmistakable: Dodge does not seek the object for itself, but for its capacity to contain a latent narrative. As in poetry, the essential lies not in the direct meaning of words, but in the space they open within the reader’s imagination. In the same way, his sculpture operates not through accumulation but through subtraction, offering the observer only the minimal condition for meaning to emerge. (…)

CONTINUE READING ↓

REVIEWS/ Stephanie LaCava: Nymph – Anatomy of a Carefully Kept Wound

Photo: Stephanie LaCava

It starts with a premonition. A subtle vertigo, like catching a childhood scent in an unfamiliar alley, or glimpsing someone in a dream who knows you better than anyone, but their name escapes you. Stephanie LaCava’s Nymph lives precisely in this space: the threshold between recognition and disorientation, between deep empathy and emotional vacuum. This isn’t a story that guides you, it pulses under your skin.

The final installment in her trilogy (The Superrationals, 2020; I Fear My Pain Interests You, 2022), Nymph doesn’t close the narrative arc-it frays it. Like a wound that refuses to heal, instead becoming a seeing eye. At its center is Bathory, Bath to those who dare come close, a being with translucent skin and a relentless gaze, named “after a blend of black metal and myth.” Her name is a mask, a cover, a charm. But also a weapon. And Bath is all of these at once, refusing the comfort of coherence.

The novel moves like a claustrophobic dream through urban and psychological interiors: stairwells, apartments, chambered rooms, flickering lights, harp music rising from the floor. Her encounter with Iggy, a figure both ethereal and corporeal, unfolds in a choreography of minimalist gestures and slanted dialogue, where every sentence is a possible key and every silence, a sealed drawer. Nothing is explained. Everything is felt. (...)

CONTINUE READING ↓

DIALOGUES/ Fakewhale in dialogue with Alex Hartley

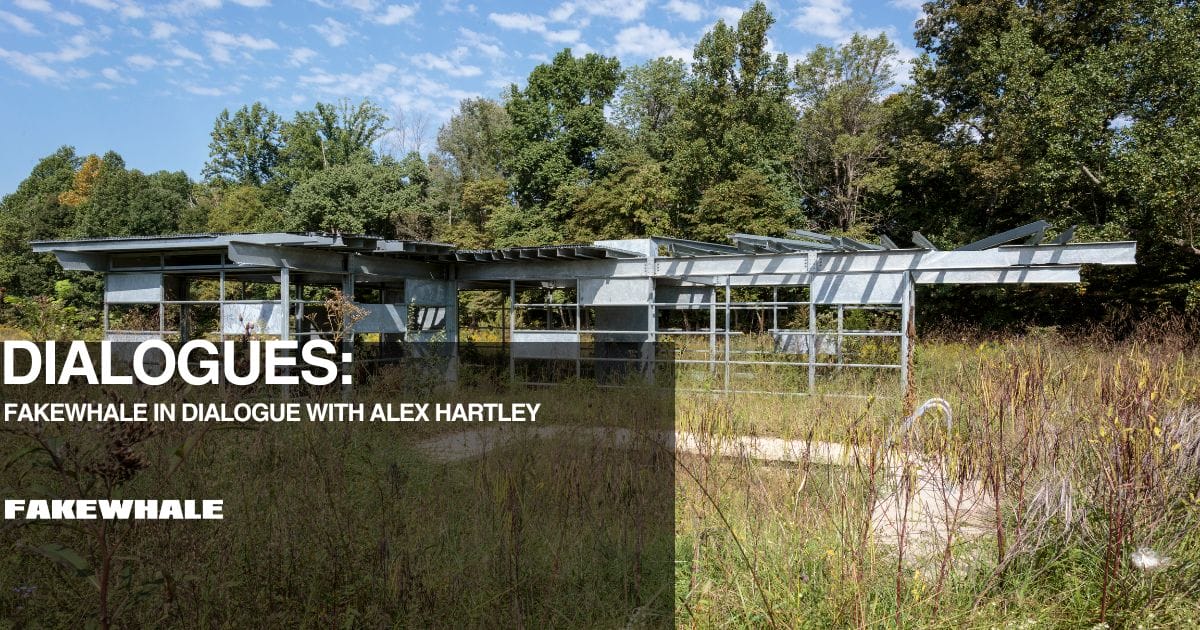

All of us just dust 2025 Recycled solar PV panels, hand dyed photographs, resin, acrylic paint, Unistrut 3500cms x 270cmx x 25cms Photo Simon Tutty

In his most recent body of work, Alex Hartley appears to undertake an operation that is as physical as it is visionary: peeling back the surface layer of the present to connect with latent energies and layered narratives, geological, cosmic, and cultural, that move through uncertain, looping, and never fully closed timelines. From the Arctic voyage of Nowhereisland to the evocative stones of Dartmoor, from modernist ruins to sci-fi architectures, his practice unfolds as an ongoing negotiation between inner and outer landscapes, between speculative imagination and the material reality of the world. At Fakewhale, we had the pleasure of speaking with him, tracing the energy of these mysterious, resonant, and deeply human connections.

Nowhereisland arrives in Portsmouth 2012 Photo Alex Hartley

Fakewhale: “All of us just dust” is a poetic and evocative title. Where did that phrase come from, and what does it mean to you in the context of the work?

I like to listen to loud music when I am working, particularly in the post-planning making phase, and often my titles relate to lyrics. I think this titled arrived via a misheard Damon Albarn/Lou Reed lyric from ‘Some Kind of Nature’ (2010) which is a great song that seems to be about the strangeness of contemporary materials. Whilst placing the images of standing stones into a painted floating cosmos I was trying to tune into the idea of the interconnectedness of everything – nothing created and nothing destroyed. I think the actual lyric that drifts in and ends the track is ‘All we are is stars’ and that somehow fell into the work and stuck to it. I find it quite helpful to hold a title in my mind whilst making a work, and for it to roll around becoming the work and the work becoming the title.

With “All of us just dust” I wanted to directly allude to the first law of thermodynamics, where energy cannot be created or destroyed – only transferred, where everything can be expressed as energy, particles, or dust. The work adopts the language of a solar array deployed by a satellite, and sets up a positive feedback loop where the power of the rocks is captured and transferred via the solar panels (ubiquitous units of energy capture). The energy moves around the work via the cosmic floating stone circle. The glass tubes are solar evacuated tubes (very common in rural settings where they heat water directly from the sun) – this solar thermal element is connected to the physical limestone rock, and leaves the question open as to whether the energy transfer is moving from the panels to the rock, rock to panels, or just part of a closed circuit of constantly flowing ancient energy. (…)

CONTINUE READING ↓

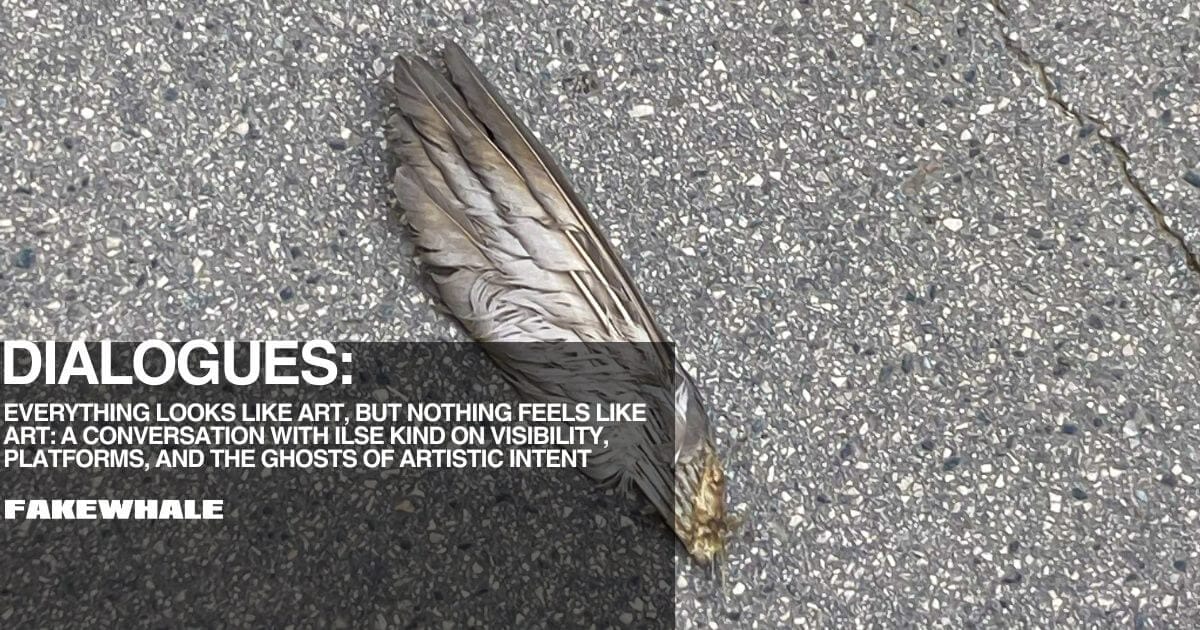

DIALOGUES/ Everything Looks Like Art, But Nothing Feels Like Art: A conversation with Ilse Kind on visibility, platforms, and the ghosts of artistic intent

There are moments when a single episode captures, with almost brutal clarity, the contradictions we live with. For artist Ilse Kind, this moment came on Instagram, a platform she had long resisted.

Kind built her practice around anthropomorphizing technologies, questioning the way algorithms influence human condition and inhabit our lives like invasive organisms. She stayed away from Instagram, fully aware of its extractive logic. But when curators began asking for a profile, she gave in. And within months, she landed an institutional show through a post. The platform she critiqued became the mechanism of her recognition.

Ilse Kind: Pride and shame collided. The works I made to expose these technologies were circulated and curated through the same algorithms they question. The museum, too, seemed more interested in how the works performed through visitors’ phone-camera lenses than in the works themselves, as if they were created for content rather than the audience present. I had flattened my works into an aestheticized, scrollable representation. And while trying to dismantle the system, I unwittingly became dependent on it, catching myself refreshing my own feed for one more hit, only to recoil at my reflection on the screen.

This is where the conversation begins. Not with a manifesto, but with a contradiction. What happens when the systems we critique also amplify us? When visibility comes at the cost of distortion? When the exhibition becomes the feed?

FW: We are living through a shift, not just in art, but in culture at large. From ontology to ecology. From what endures to what circulates. From intent to performance. In this landscape, the artwork becomes indistinguishable from the post, and the artist from the user.

But this tension is not entirely new, the need to be seen, the mirror effect, the craving for response, isn’t unique to social media. Perhaps even before the digital era, our relationship with images was shaped by dependency, a hunger for approval, and performativity? (…)

CONTINUE READING ↓

GALLERY/ Ian Margo: d/wb project Abstraction, Mediation, and the Spiral of Technoculture

Ian Margo, d/wb project, installation view, 2025

The next Solo Release curated by Fakewhale presents d/wb, a project by Ian Margo that unfolds as an inquiry into the interwoven domains of artificial intelligence, cybernetics, semiotics, and technological mediation.

Developed across Madrid, London, and San Francisco, the project resists reduction to a single category. It operates simultaneously as digital artwork, philosophical speculation, and experimental semiotics.

At its foundation, d/wb is a cycle of three video works: The Wet Box, Third Extension, and Fieldware, together articulating a spiral of abstraction.

Each work explores how signs are generated, abstracted, and activated as vectors of language, value, and perception. The trajectory moves from liquidity, to recursion, to distributed field, reframing abstraction not as simplification but as an operative force that sustains technocultural imaginaries and contemporary economies.

The cycle also manifests through precise technical construction.

The Wet Box (10:10 min, 4K, single-channel) draws on generative AI, text, and sound manipulation to stage the liquid condition of the sign. Built from noise and low-resolution fragments, it performs abstraction as a cybernetic gesture that unsettles cognition and reconfigures language.

Third Extension (8:42 min, 4K, single-channel with the possibility of three-channel expansion) layers images and text boxes to artificialize the face, enacting recursive processes of encoding and resignification.

Fieldware (11:00 min, 4K, single-channel with the capacity for fifteen auxiliary channels) reaches the widest expansion. Up to sixteen parallel streams operate as extensions of the main video, dispersing image and sound into an immersive environment. Developed in collaboration with Alexandre Montserrat, its sonic design intensifies a fractured rhythm where continuity gives way to collapse and resonance.

Ian Margo, d/wb project, installation view, 2025

Through this framework, d/wb positions video, sound, and generative systems as active forces of mediation. What emerges is a framework in which signs are not stable objects but dynamic processes that reorganize value, subjectivity, and collective perception.

By activating both conceptual speculation and material experimentation, Margo situates his practice at the intersection of artistic production and technocultural critique. To expand on these foundations, we engaged Ian Margo in a series of questions that position d/wb within a deeper Dialog Flow, tracing the conceptual and technical dimensions that shape his work.

Fakewhale: Your practice moves fluidly between research, writing, design, and digital production. When you think about your trajectory so far, how do these different domains come together in shaping your language as an artist?

Ian Margo: I believe that artistic production is intrinsically bound to research, so much so that both practices become inseparable disciplines. For me, artistic production is a field of action. As Vilém Flusser suggests, an action, an activation, is always a modification of substances. In this sense, my practice operates through aesthetics, understood as the study of what is perceptible. Thus, the artistic process becomes an act of activating and experimenting with the medium itself, with the aim of recoding formats and exploring what becomes possible when reality is mediated and made accessible through the senses.

Over the past year, my research has led me to delve into various theories of language, stemming from an initial interest in technology and digital as well as cybernetic media. My proposal is, above all, a pursuit of honesty toward the medium: an effort to recognize its limits while also exploring those limits as material for the development of artistic discourse. My work does not operate on separate layers—research, design, and production are not distinct stages but rather interconnected dimensions. Each contributes material from which the work is built. These materials are both technical and conceptual—a distinction that is increasingly difficult to maintain, since in both cases a similar act of activation is required. Ultimately, my interest lies in experience itself, for it is within experience that the boundaries of the possible are reconfigured. I seek to construct a landscape that is beautiful and sincere, one that extends the geometries of the processes that constitute it, that expands the frame—the context—and that continuously questions discourse in order to generate something new. I aim to generate movement among my materials—divergent, even distorted directionalities; a translucent unfolding; an opening to what lies within (or without, which is the same). My practice is grounded in the principle of mediation: words can only say what their own properties lay bare. (…)

CONTINUE READING ↓

That wraps this week’s issue of the Fakewhale Newsletter, be sure to check in for the next one for more insights into the Fakewhale ecosystem!