The Ninth Hour” (1999) by Maurizio Cattelan, exhibited at the Kunsthalle Basel in 1999. © Photo Attilio Maranzano.

Sculpture, more than any other medium, has for centuries embodied the illusion of stable, compact, possessible presence. Its strength was also its vulnerability: matter enduring through time instantly becomes fetish, monument, consensus. Yet the twentieth century revealed that sculpture does not die with the loss of the object; today it reinvents itself as condition, as operator, not merely occupying space, but producing it.

In this framework, sculpture ceases to be a figure against ground. It becomes the very logic of grounding, the continuous generation of thresholds where perception, thought, and matter briefly coincide. The center is no longer a point to be reached, but a structure continually produced by relations. Sculpture, in this sense, is not the presence that resists time, but the operative event that gives time, space, and meaning their form.

DIALOGUES/ Fakewhale in dialogue with Paula Ferrés

Ferrés, Paula. (2025). Volumetric digital scene. Volumetric Representation of Digital Spaces [Screenshot].

We have been closely following the research of Paula Ferrés, whose project Volumetric Representation of Performative Spaces investigates how image-based and scanning technologies transform performative environments from ephemeral, embodied experiences into permanent digital residues. Her work challenges traditional regimes of documentation and archiving, opening up new possibilities in which memory is no longer framed as objective and complete, but as fragmentary, co-authored, and performative. At Fakewhale, we had the pleasure of engaging in conversation with her to explore not only the theoretical and methodological framework behind her research, but also the broader implications it has for spectatorship, presence, and the ways we design, record, and remember space.

Ferrés, Paula. (2025). Volumetric digital scene. Volumetric Representation of Digital Spaces [Screenshot]

Fakewhale: In your work you emphasize that the transition from physical to digital space is not merely a technical translation, but an ontological transformation of space itself. How did this awareness shape your methodological choices throughout the research?

Paula Ferrés: While performative spaces are live actions based on presence, their spatio-temporal qualities are reversed when digitized, shifting from ephemeral and physical, an embodied action to permanent and digital when visualized. I therefore needed to get closer to understanding the shift from presence as a live spectator to consuming a space through digital means. Instead of aiming to reproduce physical reality, I focused on approaches that could preserve the relational, temporal, and performative qualities of space, while also exploring how these are altered through digital mediation. This led to a sequential exploration of different capture tools, culminating in volumetric scanning, which allowed me to interrogate both presence and representation while incorporating audience perception as a co-creative agent. (…)

CONTINUE READING ↓

DIALOGUES/ Fakewhale in dialogue with S. Mercure

Extraction Equipment, 2024.

In S. Mercure’s work, the exhibition space is never a passive container, it becomes a sensitive surface, a listening body, an active agent of transformation. His pieces do not simply inhabit space; they absorb its invisible residues, dust, humidity, shadows, vibrations, translating them into gesture, image, and pigment.

At a time when the sterile whiteness of the white cube seems intent on erasing all traces of time, Mercure intervenes precisely there: where architecture seeks invisibility, he reveals its memory. In our conversation with Fakewhale, we delved into these quiet gestures, this material and poetic archaeology, where each work emerges from a singular, unrepeatable relationship with its context. Here, even documentation, understood as the construction of a reality, becomes an integral part of the work itself.

SevenSites_mix_01, 2025. Water, wall powder, PVC, frame, 12 × 16 in.

In your artistic practice, the exhibition space is never a mere container; it becomes a material to be shaped and revealed. What does it mean for you to work with this kind of “physical intangibility,” and how has your research in this direction evolved over time?

The exhibition space has never been a mere container. Since art history cannot be fully understood without considering the place where art is received, it seems impossible to reduce it to a space of reception. For me, and I’m convinced for many others, the white cube is an object of fascination. I became interested in it by researching its evolution, both through its representation and its role in disseminating artworks on digital platforms. While this is a topic to revisit, my current practice developed from this core idea: even when fully constructed, fictional, or physically inaccessible, the white cube continues to inform the work, infusing it with content and meaning. From this perspective, I seek to reaffirm a physical link, a tangible interdependence between artwork and its presentation site, that is, to create work that materially emerges from its context. The challenge lies in finding an element constitutive of the space, yet imperceptible or symbolic. The white cube is designed to be as neutral as possible, so as not to “contaminate” the work it presents. This invisibilization of its architectural features fascinates me, and over time I’ve become increasingly sensitive to it. When visiting exhibitions, I began to observe the display structures more than the artworks themselves. Paradoxically, the identity of the space often reveals itself most fully in emptiness, when it seems there is nothing left to see. (...)

CONTINUE READING ↓

Authors' Insights explores experimental practices spanning sculpture, installation, video art, and transdisciplinary research. As part of the Fakewhale LOG, it provides writers, curators, and art professionals a platform to exchange perspectives, driving deeper engagement with contemporary critical discourse.

Are you a writer, curator, or art professional? Do you have a unique perspective to share or a critical reflection that could enrich the contemporary debate? Fakewhale invites you to contribute to the new “Authors Insights” section. Reach out at [email protected]

Installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2025; image: Eberle & Eisfeld. From front to back: Anawana Haloba, Looking for Mukamusaba – An Experimental Opera, 2024/25. © Anawana Haloba; Sammlung Hartwig Art Foundation; Margherita Moscardini, The Stairway, 2025. © Margherita Moscardini; Gian Marco Casini, Livorno; Armin Linke, Negotiation Tables, 2025. © Armin Linke

From rhetoric to whisper, the 13th Berlin Biennale adopts a deliberate posture of political engagement. It looks sideways, renounces slogans and the monumentality of frontal denunciation, and instead prefers a critical discourse whispered in the ear. This edition investigates fugitivity, understood as a cultural capacity to evade and reimagine oppressive frameworks. It is described as the ability to construct illegality within contexts of unjust laws, like a cunning fox finding divergent solutions in moments of danger. An artwork, for example, can establish its own laws in the face of legalized and systematized violence.

Curators Zasha Colah and Valentina Viviani stress that the concept of the 13th Berlin Biennale is not a statement or a thematic frame, but rather a true operational strategy for disentangling from multiple institutional pressures. Following the technique of foxing, a strategy inspired by the fox’s ability to elude capture, the curatorial team decided not to reveal the artists’ names until the very end, despite heavy pressure from the press, in order to protect both their works and their loved ones (many relatives of the participating artists still live in the regions under scrutiny). As Viviani writes, “to encounter implies the unforeseen quality of the meeting… like when we encounter a fox in the city at dawn.” This notion of the encounter – sudden, fleeting, transformative – frames the Biennale as a space where both artists and audiences carry away the traces of what they have met. For many artists in the Biennale, research is not merely thematic; artistic practice becomes a way of living, and vice versa. Their investigations merge with lived experience, and in several cases pseudonyms are used to protect their identities.

Opening of the 13th Berlin Biennale, Han Bing Cabbage Walker, Walking the Cabbage in Berlin, 2025, Part of the Encounters series: June 13, 2025, 8 pm, 13. Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2025. © Han Bing & Kashmiri Cabbage Walker; image: Studio Replica

In this shift from frontal denunciation to lateral critique, one aspect I especially admired in Colah and Viviani’s curatorship of the 13th Berlin Biennale is tenderness. In his book The Power of Cute (2019, Princeton University Press), British philosopher Simon May argues that “the cute” offers a playful escape from pressure. Cute does not shout, but it resists. It embraces ambiguity, flirts with the unspoken, and allows fragile, hybrid identities to take shape. It does not march, but slips into structures, softens them, ridicules them. It is a form of soft power that counters oppression with the strength of sweetness, the disobedience of play, the seduction of tender gestures. (…)

CONTINUE READING ↓

REVIEWS/ BENASSI LIBERO! Aesthetic of Friction at Palazzo Ducale, Genova

Installation view: Jacopo Benassi, Libero!, Palazzo Ducale Loggia degli Abati Genova, 2025, Photo by Fakewhale

“Today I feel free. I’ve freed myself from a certain kind of photography, but without bitterness. Maybe I no longer need to define myself through any one medium. Maybe just free. Yes, free.”

This statement, made by Jacopo Benassi at the close of a recent interview, echoes throughout every corner of his exhibition at Palazzo Ducale in Genoa, like a quiet yet uncompromising mantra. And yet, the freedom that permeates Jacopo Benassi libero! (Loggia degli Abati, 12 July to 14 September 2025) is anything but light. It’s a scratched, hard-won freedom, built from raw materials, stubborn choices, and images that refuse to be merely looked at or tamed.

Installation view: Jacopo Benassi, Libero!, Palazzo Ducale Loggia degli Abati Genova, 2025, Photo by Fakewhale

From the very beginning, visitors are forced to reconsider their role. One of the first works encountered is Villa Croce, an installation created during Benassi’s residency at Palazzo Ducale in June 2025. It takes the form of a narrow tunnel saturated with graffiti, orange light, and slogans that feel ripped from a street protest. There’s no contemplative distance here, you are thrown directly into the body of the work, without protection. It’s a bold poetic stance.

“I can’t plan my work rigidly, because the process is entirely intuitive. I only understand what I want to do when I’m physically in the space.”

The arrangement of the works is both coherent and confrontational. The photographs, all strictly black and white, are mounted on raw wooden frames, wedged into crates, strapped with industrial belts. They’re not hung, not isolated, never singular. They’re “locked in,” as if awaiting a shipment that will never come. It’s a visual barricade, every image jammed against another, forming layers that deny any singular point of view. (…)

CONTINUE READING ↓

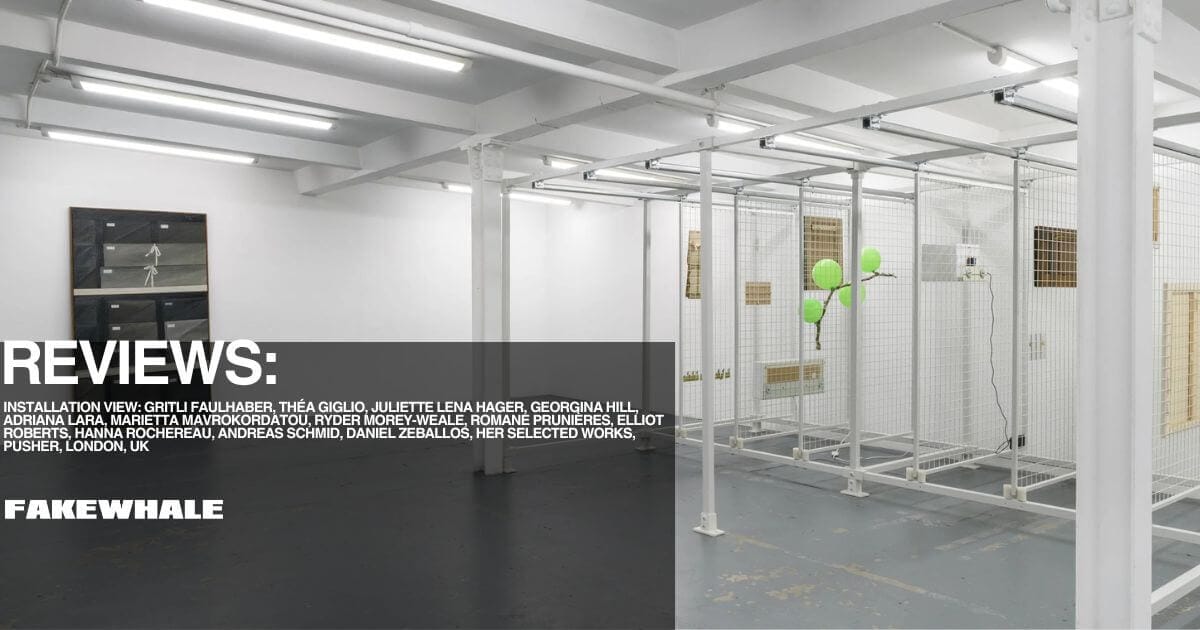

REVIEWS/ Her Selected Works: Pusher, London

Installation view: Gritli Faulhaber, Théa Giglio, Juliette Lena Hager, Georgina Hill, Adriana Lara, Marietta Mavrokordatou, Ryder Morey-Weale, Romane Prunières, Elliot Roberts, Hanna Rochereau, Andreas Schmid, Daniel Zeballos, Her Selected Works, Pusher, London, UK

There’s something humbly radical about walking into an exhibition that openly claims to have no theme. No thesis, no curatorial frame imposed from above, no aspiration to coherence. Just a series of works arranged on storage racks, not hung paintings, not monumental installations, but objects housed like archival materials, waiting to be pulled out, examined, forgotten, or rediscovered. And yet, in this deliberate suspension, in the quiet care of a selection without declarations, a subtle order emerges: an alphabet of silent things.

Installation view: Gritli Faulhaber, Théa Giglio, Juliette Lena Hager, Georgina Hill, Adriana Lara, Marietta Mavrokordatou, Ryder Morey-Weale, Romane Prunières, Elliot Roberts, Hanna Rochereau, Andreas Schmid, Daniel Zeballos, Her Selected Works, Pusher, London, UK

Her Selected Works, the inaugural exhibition at the new Pusher gallery in London, is a curatorial gesture by Carlotta S. that seems to speak more about preservation than presentation. The racks, custom-built for the space, evoke the backstage of art, storage, the pause between moments of visibility. This isn’t a show to be followed like a narrative, but deciphered like a dictionary: word by word, piece by piece, in a non-linear but natural sequence, as if each work belonged to an invisible taxonomy. (…)

CONTINUE READING ↓

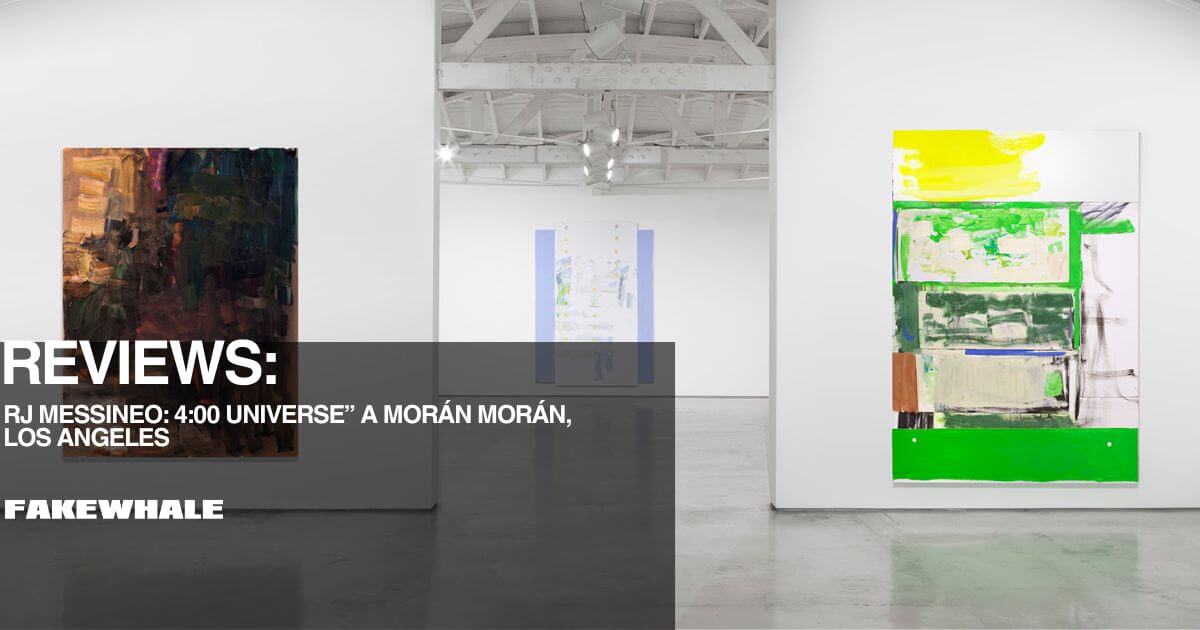

AUTHORS/ RJ Messineo: 4:00 Universe” a Morán Morán, Los Angeles

Every day, at four in the afternoon, something fractures. It’s a suspended hour, almost capricious: too late for full daylight, too early for nightfall. That’s when the light bends, orange, pink, and the world outside the window seems to stop breathing for a moment. In that chromatic pause, that motionless shimmer, lies 4:00 Universe, RJ Messineo’s exhibition at Morán Morán in Los Angeles. Ten large-scale works unfold like a visual, emotional, and meteorological calendar, born from nearly a year of looking and listening. But the viewer is never just a spectator: it’s the artist’s gaze we inhabit, filtering reality through a threshold, the window of her studio, and offering us a vision that is partial, and for that very reason, more true.

Installation view, 4:00 Universe, 2020, Photograph courtesy of Morán Morán

The exhibition space is hushed, muffled. The large canvases follow one another like sensitive walls, without clamor. These works don’t shout; they murmur. Carefully modulated lighting accompanies the tonal shifts of the paintings, enhancing the impression that time itself trickles along the edges of the frames. There is no forced path, only drift. One walks as through the chambers of memory, where everything blends: interior and exterior, matter and recollection.

The layout imposes no hierarchy, but reveals subtle relationships. The paintings converse like windows facing the same street on different days. Some are structured in sections, scored by grids recalling window frames, most notably in 4:00 Universe (2020), the centerpiece of the show. This four-panel work charts winter: the browns of fallen leaves, the clear or milky sky, the quiet veins of Troutman Street beneath the skin of the city. And then, at four, the flash, an eruption of vivid pink, a brief incandescence that transforms the mundane into apparition. (…)

CONTINUE READING ↓

REVIEWS/ Wolfgang Tillmans at the BPI – Centre Pompidou, Paris

Installation view: Wolfgang Tillmans at the BPI – Centre Pompidou, Paris

Some places feel less like they’ve been lived in and more like they’ve been dreamed backwards, each step already a fading memory. The Bibliothèque publique d’information at the Centre Pompidou is one of them. No library card is required here: just patience, a wait among queued-up bodies, minutes ticking by under a suspended light that has always felt both temporary and timeless. We came here to look for a book or a power socket, to escape the cold or to find a shard of concentration. But also to become part of a nameless, shared intimacy, the kind only certain public spaces can offer. Wolfgang Tillmans has chosen precisely this setting, the BPI, now about to close for five years, as the stage for his exhibition Nothing could have prepared us, Everything could have prepared us. And he’s done more than simply exhibit: he’s allowed the place to reveal itself for what it’s always been. An archive of presences.

Crossing the threshold of the BPI today means entering a space emptied out and reimagined: the once-crowded bookshelves and desks have been replaced by images, arranged not in hierarchy but in gravitational pull. It’s an absence that breathes. A horizontal maquette guides us into the exhibition, highlighting in lilac what remains, furniture selected by the artist, traces of time, fragments of purpose. Tillmans’ first move is to restore perspective to vision, in a space that usually drowns it.

This exhibition holds a double memory: of the artist and of the site. At its core sits an installation made from the old self-training computer desks. On one side, a video library of Tillmans’ work; on the other, filmed portraits of BPI users. Though recently staged, the footage feels like relics: focused faces, stifled laughter, unaware glances. As if the artist sought to register the echo of a daily gesture before it disappears. The observer becomes the observed. The user becomes the image. And the library, once a container, becomes the subject. (…)

CONTINUE READING ↓

EXPLORE THE LATEST ARTICLE↓

That wraps this week’s issue of the Fakewhale Newsletter, be sure to check in for the next one for more insights into the Fakewhale ecosystem!